MATISSE GOLDFISH

Much modern painting is concerned with fluidity.The sloughing off the direct representation of the world's extension and objects lead towards immersive, inner landscapes.Removing the grounding of the horizen line created spaces allied to aerial or the aquatic; brightly coloured memories of objects were left floating, with colour seeping through space or bound by line and held tightly within it.The suspended images that resulted are often underpinned by a sensation that they have been brought forward in response to the viewere's sight. Rather than a scene stilled for contemplation painting became a container for colour- moments ,an ever forming ' now '.

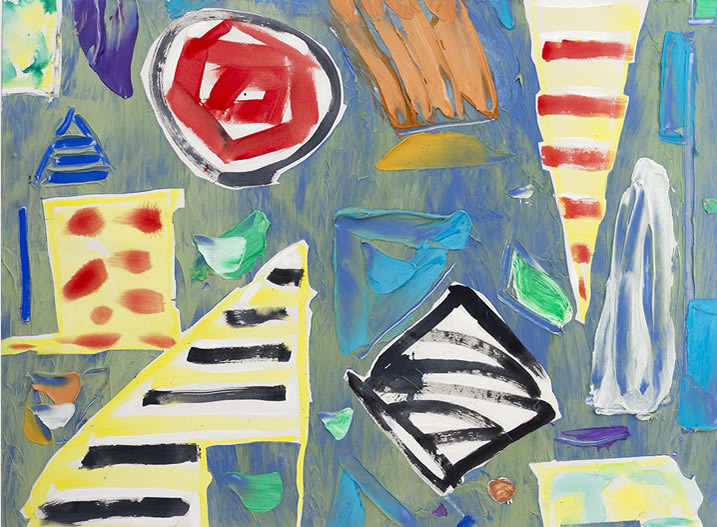

The bright artifcial colour in Graham Boyd's new paintings belongs in the above tradition.Behind each lies a fairly consistent process.First a thin wash of colour,then some areas are masked off, before the appliance of a thick layer of gel. Boyd paints on and into the gel whilst it is wet, his lines and colour shapes merging with it, or being carved into it.He likens the process to fresco -- with the canvas laid flat on the floor he has to work quickly as soon as he is left with an unamenable surface, tough and ridged. After the gel has hardened Boyd can continue to work by returning to the areas that have been masked before the gel was applied, or by sticking bits of painted canvas to the picture, often collaging parts cut from otherwise failed paintings. The thick surfaces and contained gesture of Boyd's recent work can be seen as a partial return to the all-over abstract divisionist paintings he made in the late fifties; the recent work can also be compared with his quasi-scientific constructions of the sixties or his methodical spray-gun paintings of the seventies. In these Boyd combined different ' rules ' or 'systems to lead to unexpected outcomes, in order to, as he puts it,' invite chance in '.

Though the recent paintings have a consistent process, this is intended to allow improvisation, not just work of its own accord,and the goal is to' let the play instinct free and open up new possibilities.'

Many of the marks seem caught up in the arrested motion the gel's ridges describe, or appear to flutter across the surface they are embedded in.Elsewhere drawing counters the gel's slickness with a pleasingly naive slightly wonky quality.This wonkiness, particularly in the areas masked off before the gel was applied, allows the shapes to stick to the surface of the picture with a sense of security- a certainty that is perhaps an inverted version of that found in collage. Boyd talked to me of the propensity of young children to draw geometric shapes, also of the checkerboards found alongside the cave-painters' bisons and hand- prints.The directness of Roger Hilton is an ackowledged influence--- one also visible in the simple patterns which fill the masked-off areas (for Boyd, Hilton is an under- appreciated artist, the pictorial intelligence he gained from an early immersion in Fench painting giving him the edge over his St. Ives contemporaries).

The shapes jostle each other across the surface, vying for your attention. As is more frequently the case with Hilton's work, on occasion they seemed to be imbued with a sort of personality similar to what we want to give to primitive organisms seen under a microscope (a less securely non representational version of the ' bringing forth ' I described in the opening paragraph). Some of the more successful large works temper their liveliness by arranging the shapes into a loose grid, often with the result that the colour can work in a more relaxed and satisfying fashion. But for me the most successful paintings -- such as Scatterdells Green -- work off grid, walk the line between sitting back and coming forward and occupy a position between order and disorder.

Sam Cornish.